Champagne Memories

Nothing will top the Millennial celebration of 1999 but we will be happy to still be popping a cork on New Year's Eve this year

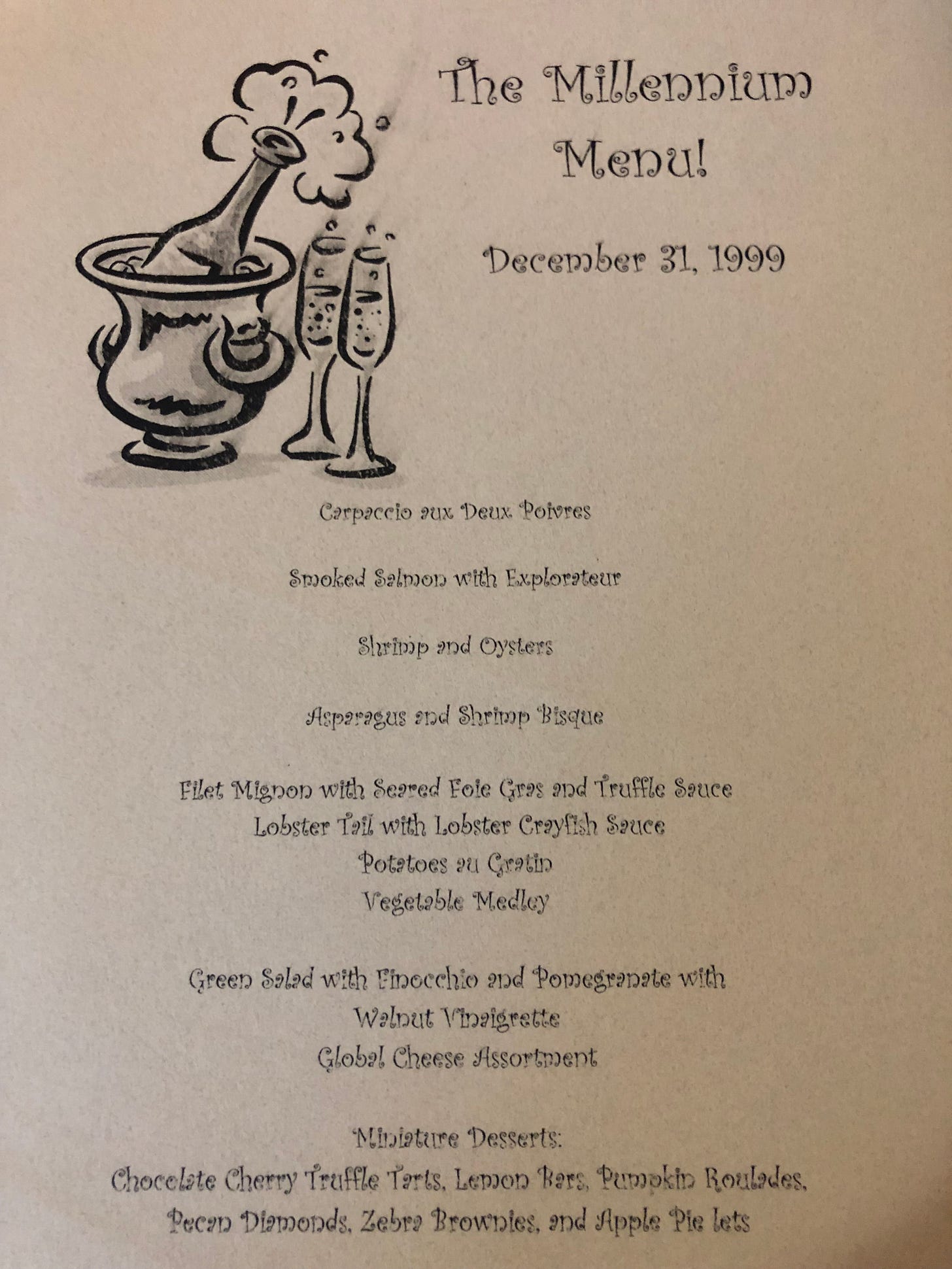

This column was originally printed in the Centre Daily Times just before the Millennium. We had a progressive dinner that New Year’s Eve, with friends who closed their restaurants—the Gamble Mill in Bellefonte and the Hummingbird Room in Spring Mills—so we all could spend time with 18 friends on that singular occasion. The food—and the wines—were fabulous as we traversed between three houses, toasting until we reached the hour of midnight around a bonfire. We won’t be popping any Dom this year in Wyoming, rather a Crémant de Bourgogne, but we will be popping corn and banging on pots and pans to ring 2024 in loud and clear.

Champagne season is here and the question of which champagne to serve on New Year’s Eve is under hot debate. Personal preference is guided by what we have experienced with champagne in the past, associations, and expectations, realized or not.

When we traveled in the Champagne region in 1985 our two sons were 6 and 4. One toted a small boombox; the other, a case of children’s books on tapes. In the stark chill of early spring, we drove through steep, chalky vineyards, listening to Gulliver’s Travels. The wooded limestone plain and plateau near the Marne River was austere, the faces of the few villagers that we saw seemed stern and reserved.

In the village of Epernay, we toured the cellars of Moet et Chandon, the boys happy to be out of the backseat. On a guided tour of some of the many miles of subterranean chambers, we noted how each bottle was held upside down in wooden racks. A white dash on the bottoms of the bottles, like a one-handed clock, indicated which way to turn the bottle a quarter turn every three days as the yeasts slowly transformed the sugars in the juice to alcohol and carbon dioxide with 90 pounds pressure per square inch.

John and I found the complexity of the process fascinating. The remuage, or tilting and twisting of the bottles for 6 to 8 weeks, forces the sediment from the yeast down onto the cork. The dead yeast cells are then removed by degorgement, when the neck of the bottle is immersed in a freezing solution. The cork is released and the pressure within forces out the frozen sediment, along with a bit of the wine. Sweetened wine, the dosage, is added to replace what has foamed out and the bottle is machine-corked with extra-large corks that must say “Champagne.”

Though we enjoyed the tour the boys were less interested and contented themselves by playing tag in the tunnels, disturbing the bats.

Our next stop was the tasting room where I had the champagne-defining moment of my life. Fully aware of the effort that went into the bottle, I tasted Moet et Chandon’s White Star Extra Dry and, like the celebrated Dom Perignon himself, “drank the stars.” Each tiny bubble danced over my palate as I savored the mineral quality of the chalky earth tempered with sweetness added by the skilled cellar master’s hand. I recognized balance and finesse. Although I had enjoyed good champagne previously, knowing the details added immeasurable depth to the experience.

Meanwhile, the boys were hungry. We found a bistro, crowded with locals who now looked much less stern to me. Throughout our European adventure the boys, dressed in bomber jackets and GI Joe caps, made it easy for us to start conversations with any adjacent stranger. Plus, the best aspect of traveling with my husband is that he is undaunted by not knowing the language. Soon we were engrossed in conversation with the French couple next to us, though we don’t speak French and they didn’t speak English. Somehow, brokenly, we communicated in German and were having such a great time with them that they invited us to their home.

The man worked at Laurent Perrier and he wanted us to stop by and drink some champagne with them. We tried to decline—the boys have to go to bed, it’s late, we don’t know these people—but how often do you get invited to go to a local’s home in the Champagne region to drink what they make?

Their home in Ay was modest and cozy. They made us welcome, gave the boys some toys, and situated us around their dining table, while we insisted that we were only there to share one bottle. One bottle, he agreed heading off to the cellar. He returned with a very large bottle of champagne, a magnum, and we all laughed and talked far into the night.

We learned much from them about daily life in the region. Through our mutually broken German we learned about the grapes and the struggle to keep them on the vine long enough to get the sugar level up. The weather in the region is much colder than any other French wine-growing area and the still wine produced from the grapes is too acidic. The addition of sugar and the resultant chain reaction of effervescence enable the growers in the region to make the most of what they have. They have made a virtue out of their necessity and created a demand that will peak on New Year’s Eve, 1999.

People all over the earth will raise glasses to the new century with the signature of celebration—French champagne. Salute!

I love your description of tasting the exceptional champagne!