The original version of this article appeared in the Centre Daily Times in 2002 and is my true confession about my own confusion about yams and sweet potatoes. I worked it all out eventually, humming this little Popeye song to myself.

Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

I must confess that I was guilty of disseminating false information during my stint in the foods lab at Penn State teaching Basic Food Preparation. Believed what I was told by produce managers, I spread misinformation to the furthermost reaches of the commonwealth and beyond.

Holding aloft an orange-skinned and fleshed, elongated, plump underground vegetable, I called it a “yam” and holding a narrower, paler, yellow-fleshed underground vegetable next to it I called it a “sweet potato”. Actually, they are both sweet potatoes and can grow in temperate climates like the one we live in.

Yams are another matter entirely, one that we must travel to the humid tropics of Central and South America or Africa to encounter. Tropical yams, the scientific name Diascorea, are related to grasses and lilies and are tubers, short, fleshy stems, that usually grow underground. The yam was one of the earliest flowering plants and spread across the continents before the big drift. They subsequently evolved independently, a fact that accounts for yams’ distinctive regional characteristics.

In Africa, where the tropical yam is a staple as familiar as our mashed potatoes, the plant is called “nyami”. Hispanic countries use a tropical tuber that they call cassava, or yucca or manioc, in the same way, as a starch to supply a neutral palette for spreading spicy sauces and stews. Variations in other tropical realms are labeled malanga, or yautia, or taro, or yamaimo.

Are you confused yet?

The sweet potato that we know has the scientific name Ipomoea batatas and is the true root of a plant that is a part of the Morning Glory family. Native to Central America, the sweet potato migrated to Europe with Columbus after his first voyage, where it was enthusiastically welcomed and regarded in court as an aphrodisiac. Henry VIII had sweet potatoes imported from Spain and made into confections.

Sweet potatoes come in two main varieties—moist-fleshed and dry-fleshed. The moist-fleshed variety has dark skin and bright orange flesh and is known in this country as yam. African slaves coined the name after one of their favorite foods from Africa, the starchy, tropical nyami, the source of our literal confusion. The dry-fleshed variety, lighter in color, starchier, and not as sweet as its orange sister, maintained the correct name, sweet potato.

An interesting fact about yams is that the late Russell Earl Marker, professor emeritus of organic chemistry at Penn State, used the tropical yam that he dug up in Mexico to lay the groundwork for a social revolution when he extracted estrogen from the plant. Called the “Father of the Birth Control Pill”, Marker was not researching population control or aphrodisiacs—but his findings happened to change the course of history.

Sweet potatoes are primarily a carbohydrate and are a rich source of vitamin A and potassium. When eaten with the skin, they are a good source of fiber. Though they look rugged, sweet potatoes have thin skin that is easily damaged. Growers cure them, that is, store them for 10 days at a high temperature and humidity before sending them to market, to help preserve them. This treatment also enhances their natural sweetness. Sweet potatoes should never be stored in the refrigerator, where they may develop a hard core and their natural sugars may turn to starch. They can be stored for about a month at a root cellar temperature of 55°. If kept at room temperature, they should be used within a week.

So, remember, class: this is a sweet potato and this, is a sweet potato. And all those yams are another story.

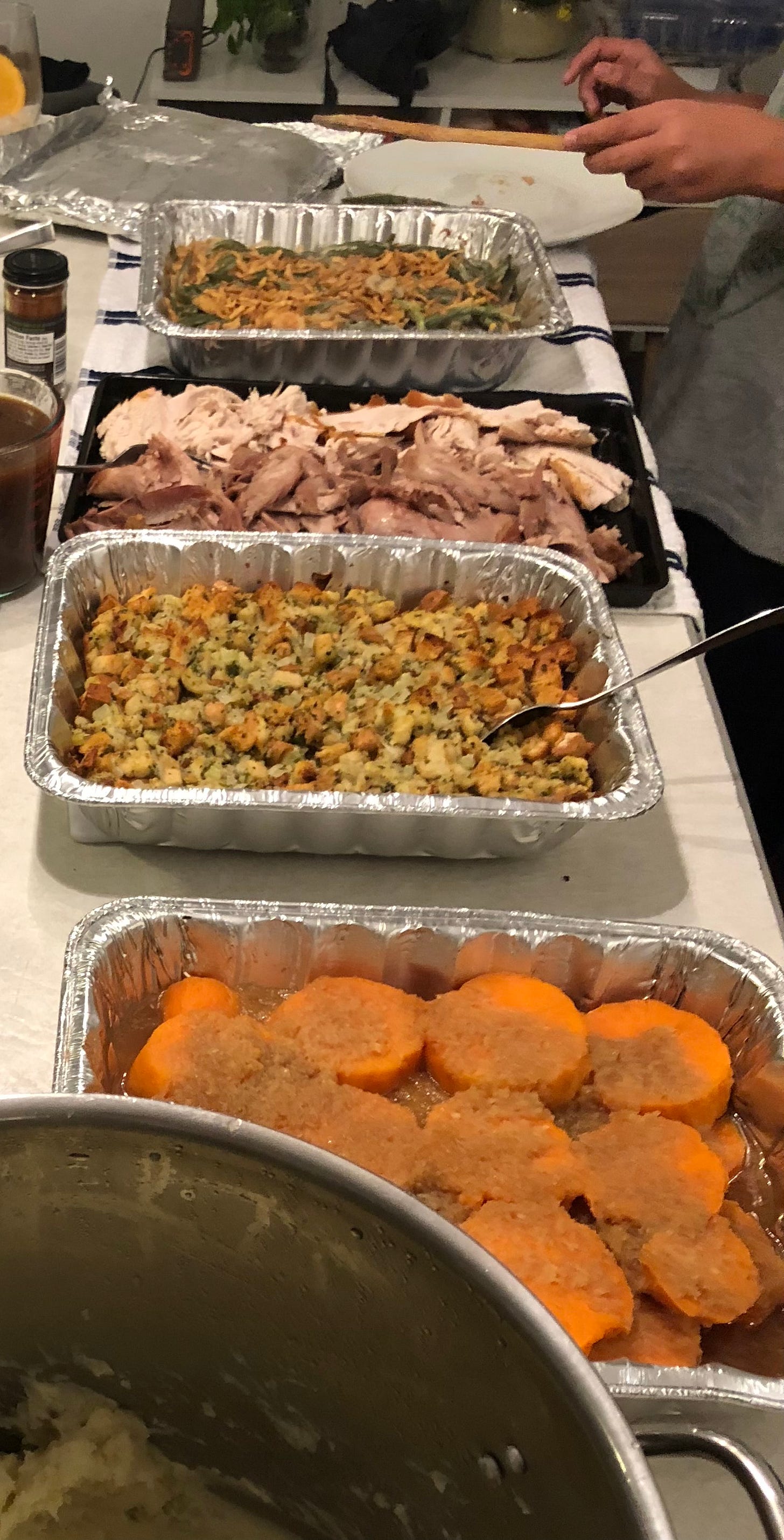

(I will have a photo of this in a day or two. It’s an easy make-ahead for Thanksgiving dinner and our son Al’s favorite sweet potato recipe. Since he is coming to Wyoming this week with his family, I’ll be sure to have them on this year’s Thanksgiving table.)

Candied Sweet Potatoes and Pineapple

Serves 12

3 pounds of sweet potatoes

one-half cup butter

three-fourths cup brown sugar

one-half cup of orange or pineapple juice

one-half teaspoon salt

Half of a fresh golden pineapple, peeled, quartered, cored, and sliced

or one 20-ounce can of pineapple chunks or crushed pineapple

Microwave the sweet potatoes in a plastic bag on medium-high power for 15 minutes, or until they test nearly soft with the tip of a knife. Allow them to cool. Melt the butter is a sauté pan and whisk in the brown sugar, the juice, and the salt. Cook until the mixture is smooth and hot. Peel the cooked sweet potatoes and slice them into rounds. Arrange slices of the sweet potatoes in a lightly buttered baking dish, alternating them with slices of the pineapple. Alternatively, you could arrange them in a baking dish and scatter the pineapple chunks over the top. Pour on the butter-brown sugar mixture and bake in a 350° F oven for 45 minutes until hot and bubbly around the edges.